Bret Hart vs Chris Benoit: WCW Monday Nitro’s Greatest Match

Wrestling is a worked sport, this is hardly a startling revelation. Two men (or women) get into a ring and essentially figure skate together, with the aim to provide the best show possible.

However there are instances when wrestling can become ‘real’. Perhaps not authentic in the sense that the winner is still predetermined, but the occasion surrounding the bout is.

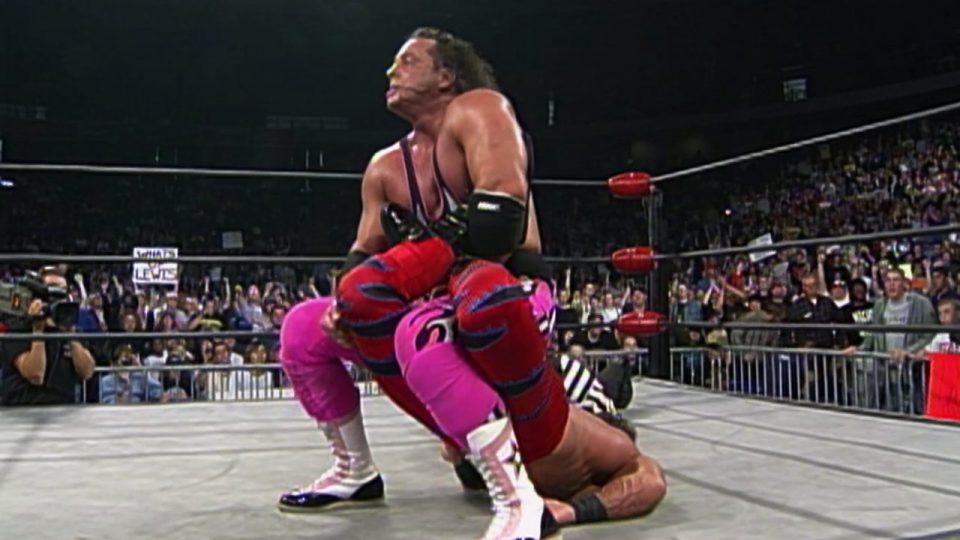

One such encounter is the Owen Hart tribute match between Bret Hart and Chris Benoit on the October 4th 1999 episode of WCW Nitro.

The significance of the match wasn’t lost on either man; the emotional dial turned up to 11. In an era where wrestling was as cartoonish as it was at the height of its late-80s pomp, the tribute match to the late, great Owen Hart between arguably the two greatest wrestlers to ever step out of Canada was so viscerally real. This was as real as the world of wrestling could possibly ever get.

Hart had seriously contemplated retiring in the aftermath of Owen’s tragic death. He was 42 years old, and had little left to achieve in the wrestling business, with his legacy as one of the greatest to ever lace up a pair of boots already cemented. Yet the Canadian also believed he didn’t want to end his storied career due to his brother’s tragedy, and thus decided to soldier on in the free-falling WCW.

By the autumn of 1999 the company’s value and TV ratings were nose-diving faster than a Benoit flying head butt. Eric Bischoff, integral to the success of the company in the mid-90s, had been let go in September and replaced by Bill Busch. The goodwill Bischoff earned from turning the company’s accounts from red to green had long since dissipated, as was WCW’s with the audience. Ratings plummeted throughout the year, as viewers switched to the WWF en masse.

With WCW running Nitro at the Kemper Arena on October 4th, Hart knew this was the perfect opportunity to propose the best tribute possible to his brother Owen: a match with fellow Canadian and Dungeon graduate Benoit. Of course this being WCW, the Arkham Asylum of ‘90s wrestling, the company had to be coaxed into allowing the match to happen, with both Hart and Benoit eventually convincing the executives that it was the right thing to do. They were allotted a 30-minute timeslot for the match, unheard of by Nitro standards for a match with no title involved.

Hart had only wrestled on several occasions in the months preceding the bout, and by his own admission wasn’t in the best physical conditioning. Furthermore, he accepted that despite being the greatest wrestler of the 1990s in North America, he could no longer consider himself the best at this stage in his career, and Hart would be relying on Benoit’s exceptional fitness and intensity to carry portions of the planned 25-minute match.

Yet even at 42, Hart was still superior to the majority of wrestlers in the big three companies, and still retained his unparalleled crispness in move execution and ability to tell a story like no on else.

If one was a fan of traditional wrestling, 1999 was a truly horrible year. Try to compile a list of the greatest matches of the year, and you would be hard pressed to find one of outstanding quality.

This year, of all years, was the nadir for in-ring brilliance in the Monday night wars. Match quality was sacrificed in the name of dramatic storylines and swerving the audience. The quality of in-ring work across the North American promotions dipped. Even on PPV, matches scarcely went over the 20-minute mark and were usually shoehorned with run-ins and gimmicks.

Hart and Benoit wanted to produce an old school, no-frills wrestling clinic, filled with holds and counter-holds, a slow burn of a match that built to an intoxicating crescendo. In essence, the wrestling equivalent of watching a season of The Wire.

This was something that the average wrestling fan of 1999 wasn’t conditioned for. They had become accustomed to 12-15 minute matches, maximum, that contained brawling through the audience for large parts. Both men wanted to turn back the clock, to a time in which they only needed each other to tell a story and not a litany of props. Bells and whistles? No thanks, just our bodies is enough.

The crowd was respectfully quiet in the opening stages of the contest, as both men felt each other out. The match was played out as babyface vs babyface, a rarity for the era, and a touching moment in the match occurs when Hart sidesteps an attempted Benoit move by holding onto the ropes – which prompts Benoit to nip up – and the pair shake hands.

As expected in a match containing these two, the technical prowess was a cut above anything else in the company. The bout ebbed and flowed with real intensity displayed throughout. Benoit in particular was impressive; in one sequence performing three consecutive snap suplexes followed by his trademark diving head butt. In another, he performed a jumping Tombstone on Hart.

Slowly, they gained the fans’ attention, and as Benoit tried desperately to put Hart into the Crossface close to the 25-minute mark, the latter brilliantly blocked his attempts and somehow got his opponent into the Sharpshooter, with Benoit tapping out in the middle of the ring.

The five-time WWF champion had strongly wanted to put Benoit over, but was told otherwise. On this night, there really couldn’t have been any other decision. But this match is one of those rare examples in the Monday night war era where winning and losing didn’t have any significance: the sole purpose of the match was to give a fitting tribute to Owen, and the pair succeeded on every level.

Emotions ran high following the bell as both men struggled to hold back tears. They embraced in the middle of the ring, and in shades of SummerSlam ’92 with Davey Boy Smith, Hart raised Benoit’s hand, however this time as the victor.

“Chris, he’s up there right now watching us,” Hart recalled telling Benoit moments after the bell in his seminal autobiography Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling.

The match was an instant classic: it was undoubtedly the greatest wrestling match in Nitro history, in addition to being the last great match witnessed on the show. Furthermore, the tribute match was the final great bout of the 20th century, and by far the best of that year, in any promotion.

He wasn’t to know it, but it was also Hart’s final dance with greatness. Within three months he would suffer multiple concussions from the likes of Kevin Nash, Sid and chief among them, Goldberg at Starrcade ’99. His last match came against Nash as WCW champion on the January 10th 2000 episode of Thunder, and he’d announce his retirement that October.

Benoit wouldn’t hang around WCW for much longer either. Sick of hitting his head against the proverbial glass ceiling, he, along with Eddie Guerrero, Perry Saturn and Dean Malenko tore up their contracts with Turner and switched sides, which in retrospect became a landmark moment in the history of the Monday night wars.

And of course, less than eight years after the bout, it became extremely difficult to remember anything involving one of the two participants with any degree of fondness. Nonetheless, despite the sad epilogue for both wrestlers and the company itself, this remains a moment that, at least at the time, was built on nothing but love for a lost brother and a lost art.

On that one October night in Kansas City, the pair reminded everyone of the mesmerising synchronicity that can happen between two wrestlers inside those ropes when everything is stripped away. A glorious reminder that there is beauty in simplicity.

Owen would’ve been proud.

This article was originally written by Emmet Gates.